Bringing the gospel to the Nukak people has had more than its share of uphills and downhills

The day I arrived in the village, a Nukak man died. A young man who shouldn’t have died. He should have lived to be an old man. But like many Nukaks before him, when faced with rejection or embarrassment, he reached for the poison. He drank it. And he died.

“There have been hundreds of Nukaks who have committed suicide,” missionary Lisa Jiménez shared. “Mostly men. For social reasons. For rejection. Hundreds of them.”

It’s a harsh reality — and one the missionaries have faced time and time again. Each time, they wished the hope of the gospel message had already penetrated the darkness of the Nukaks’ hopelessness. But it hasn’t. Not yet.

The early days

Reaching this monolingual people group was not an easy task. The language barrier was compounded by their nomadic lifestyle. Living scattered throughout the jungles of Colombia in small family clans, they wandered in search of fruits in season, sleeping in hammocks under makeshift houses thatched with huge plantain leaves.

The initial contact with the Nukak people was back in the early 1970s. It didn’t go as planned. Though one of the early missionaries with the Nukaks, Danny Germann, was pleased at the seemingly smooth exchange of gifts — the accompanying poisoned dart in his neck wasn’t quite so pleasing.

Tense moments continued as relationships were established between the missionaries and the feared Nukaks. One night in particular stands out in Andrés Jiménez’s mind. He had his foot on a log and a Nukak man took a swing at it with an axe, barely missing Andrés’ foot. And then the man started laughing. Laughing and laughing.

“I was always afraid of him walking behind me on the trail because I didn’t know what he might do to me,” Andrés said.

“It’s like he was trying to see how Andrés was going to react,” added Lisa, Andrés’ wife. She went on to explain that “now he’s like this calm old grandpa, like he wouldn’t harm a fly. But when he was young. …”

Despite the tensions, the missionaries wanted to live in Nukak territory, but between the ever-prevalent malaria and recurrent guerilla activity, keeping missionaries in the tribe proved to be a constant battle.

This came to a head in 1985 when NTM missionaries Tim and Bunny Cain, Steve Estelle and Paul Dye were kidnapped by guerrillas. All missionaries living in remote jungle locations were evacuated. The team of missionaries among the Nukaks found themselves uprooted and forced to leave a people they had grown to love.

As time passed, it became evident that the missionaries could not return to Nukak territory due to the guerrilla activity. So how would the ministry continue?

Thinking outside the box

The answer came to the missionaries as they observed the Nukaks seeking medical attention in small guerrilla-controlled towns dotted along the rivers. Where could the Nukaks receive medical attention that would also offer a measure of safety to the missionaries? A survey trip was conducted. Only one small jungle town fit the criteria. Luis and Elizabeth Trujillo were the first to make the move. They remember those early days.

Luis reminisced, “In 1996 we moved to a small jungle town situated on the border of Nukak territory to continue studying language, but there just weren’t any Nukaks around. So we started to pray, ‘God, give us a Nukak family to study with.’

“One day we were walking in town and saw a Nukak family. We followed behind them as they went from restaurant to restaurant watching people.

“I said to my wife, Elizabeth, ‘When they are somewhere private, we’ll approach them and talk to them.’

“And then they got to a quiet place and we called out to them in Nukak. They asked us where we lived. We told them, and asked if they wanted to come to our house. They came.”

Before long the missionaries were making regular afternoon visits to the hospital. It was rare not to find two to five Nukaks there. The Nukaks would stay for about a month, and once they recuperated, return to the depths of the jungle, far from contact with outsiders. Though it was challenging to have a revolving door of language helpers, the missionary team rejoiced that contact had been reestablished.

Challenging aspects

Eventually one large family clan showed up and stayed, but they were landless and culturally at odds with the Colombian townspeople. The mayor of the town made a generous offer, allowing the Nukaks — though not the missionaries — to live temporarily on his personal land. Temporary has extended to the present day.

Living outside the community, the missionaries’ exposure to culture and the daily lives and routines of the Nukak people is hampered. Add to that the fact that the Nukaks continue to be semi-nomadic, leaving for months at a time when the jungle fruits are in season, and it’s easy to see why years have passed by and the missionaries still find themselves immersed in culture and language acquisition — but not yet ready to share the gospel message.

Culture and language blend together

The missionaries are well aware of the need for proficiency in both culture and language. One without the other just doesn’t cut it. They are equally important. Suso Rojas had a great example to share.

“In their culture, they don’t like to remember someone who has died,” Suso told me. “I kept using the Nukak word for a hole, and since we have a lot of holes on the land where we live, I used that word a lot. But there was a man who died that had that same word for his name. So the Nukaks reprimanded me, ‘Don’t say that word.’” They gave Suso a different word to use because they didn’t want to be reminded of their dead loved one.

Do you see how learning the language without the culture would be problematic? Imagine how this cultural taboo would affect a language over the years. And this is but one example.

To effectively communicate in the language, you must also understand the culture. To clearly understand and learn the culture, you need to be exposed to it. And it stands to reason that if you aren’t living among the people, you handicap the learning process. So what options did the missionaries have?

Property for a purpose

If they could not live among the Nukaks, the missionaries figured the Nukaks could come to them. So in 2008 the team purchased a good-sized plot of land. Suso and Elga Rojas were the first to build a house and move there, and later Luis and Elizabeth Trujillo and Andrés and Lisa Jiménez joined them. Jack Foster and Colin and Megan (Jiménez) Rogers still live in the nearby town.

If it weren’t for the cultural implications, the missionaries would have just asked one of the Nukak families to join them, but by inviting them, they would become responsible for them. They had no desire to create an environment where the Nukaks were dependent on the missionaries. On the contrary, they wanted the Nukaks to learn how to live responsibly alongside the Colombian community, yet without leaving their cultural identity behind.

“We prayed that the Lord would put it in the heart of one of the Nukak families to ask if they could live with us, and that is exactly what He did!” Lisa wrote. They wait for another to ask.

Having the Nukak family living in close proximity — at least when they’re not off on a nomadic trek through the jungles — has been greatly beneficial in the missionaries’ progress toward proficiency in culture and language. Frequent visits are still made to the Nukak community to continue building relationships with individuals and the community as a whole.

“The vision of this project with the Nukaks living here with us is about discipling them in everything we can,” Andrés said. “First with material things, and then, when we have the language ability, we can move on to spiritual things. We are looking to the future.”

A legitimate question

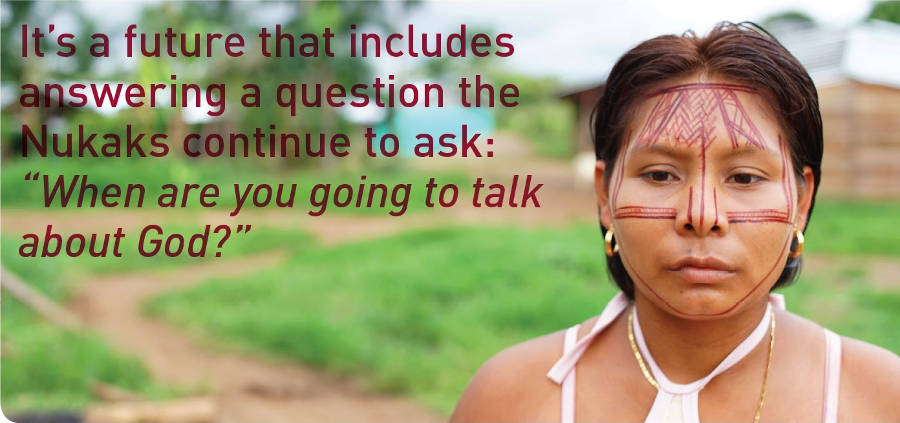

The missionaries are looking to a future where they are finished with formal culture and language study and ready to move into Bible translation and lesson preparation. It’s a future that includes answering a question the Nukaks continue to ask: “When are you going to talk about God?”

That day is coming. When I asked the missionaries for prayer requests, reaching proficiency in culture and language ranked the highest. There was an urgency behind their request. They have too many stories that end with “but so-and-so drank poison and died.”

They want a different story to tell. They pray for the day when they can answer the Nukaks’ question. They pray for the day they can clearly verbalize God’s story in the Nukak language. And they pray for the day the Nukaks’ eyes light up as they fully grasp the scope of God’s love and His message of hope. Would you pray for that day?